It is not a given that the inflation outlook is much worse now than it was before the collapse of WOW Air. If the wage rises negotiated this spring are not excessive, there is a growing likelihood that the Central Bank’s (CBI) policy rate will fall as the economy slows down.

Is further weakening of the ISK inevitable?

In the past few days, it has been widely asserted that WOW’s insolvency at the end of March will cause inflation to rise higher in coming quarters than it would have otherwise. The main rationale for this view is that lost foreign exchange revenues will erode the current account balance enough this year that the ISK will have to give way to compensate.

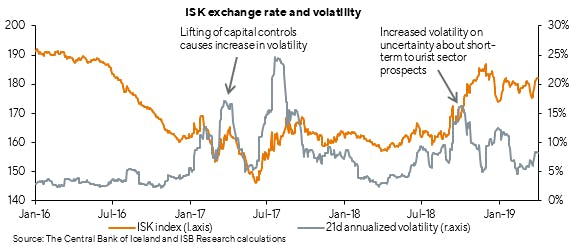

The initial effect on the FX market does not support this hypothesis, however. Certainly, the ISK dipped noticeably just after the news broke, until the CBI intervened in the market later that day. Since then, however, the market has calmed down, and the exchange rate is broadly where it was in mid-January.

The fact is that forces other than the trade balance often have a stronger impact on short-term exchange rate developments. Among these are investment-related capital inflows and outflows. Roughly estimated, this year’s direct and indirect FX revenue losses due to WOW’s collapse could run to ISK 50-80bn. This is offset, though, by a reduction in inputs needed to generate these revenues and a reduction in goods and services imports stemming from weaker ancillary economic activity, which could total up to half that amount. In spite of this, we do not expect a current account deficit this year unless the contraction in tourism proves to be deep and protracted.

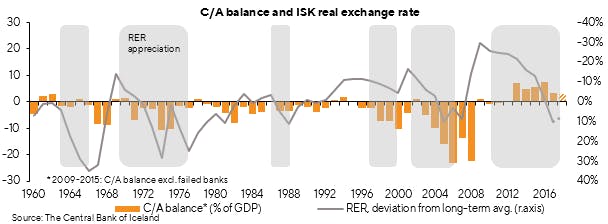

Iceland’s recent economic history includes years when the ISK has weakened in spite of a healthy current account surplus (2018) and years when the ISK appreciated while the current account showed a sizeable deficit (2004-2005). To be sure, these variables pull on one another and ultimately seek equilibrium, although that equilibrium tends to disappear as soon as conditions change. Bearing in mind that the ISK has already depreciated by approximately 10% in trade-weighted terms since mid-2018, and assuming that the current account does not show a deficit this year, we think it can be argued on strong grounds that outflows due to pension funds’ and other resident entities’ foreign investment and inflows due to non-residents’ investment in domestic firms and securities could be the determining factor in whether the ISK weakens further this year. We think it quite likely that there will not be a significant further depreciation in 2019.

Inflation could remain moderate …

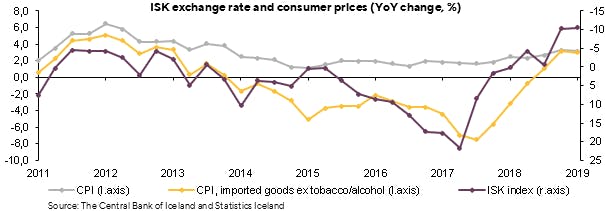

If the ISK does not weaken substantially over the remainder of this year, imported inflation will taper off gradually. The exchange rate pass-through from the ISK depreciation to imported goods prices has thus far been more modest than we expected. Effective — and increasing — competition in the retail sector has made its mark, in our opinion, as has the growing uncertainty about domestic demand. By the same token, inflationary pressures from house prices have eased, and the outlook is for house price inflation to slow still further. The short-term impact of WOW’s collapse includes reduced private rental activity through Airbnb and the possible departure of foreign workers from Iceland. Overall demand pressures in the economy will presumably subside accordingly.

… if wage negotiations are brought to a favourable conclusion …

In sum, there is one main factor (provided that the ISK holds its ground) that could fuel inflationary pressures in the near future: firms’ wage costs. Over the past five years, wages in Iceland have risen annually by nearly 6% over and above inflation. As a result, households’ purchasing power is now nearly 30% greater, on average, than it was at the beginning of 2014. The fact that the ISK depreciation in H2/2018 has markedly improved Icelandic exporters’ competitive position but has not eroded households’ purchasing power more than has already occurred is a very favourable combination of circumstances, and one very different from the usual situation at the end of the Icelandic business cycle. In view of this, employees who are reasonably well positioned can be satisfied even if their purchasing power does not increase significantly this year.

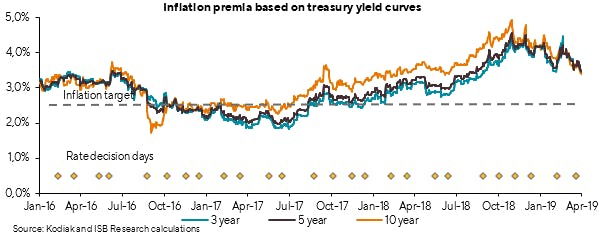

If the wage negotiations currently underway are concluded with modest wage increases focused on improving conditions for those who have the least, as appears to be in the cards at present, we think it quite likely that inflation will not rise substantially over the remainder of the year. Assuming that others share our opinion and inflation expectations subside again, as the bond market seems to indicate, economic policy should focus increasingly on stimulating the economy, which looks set to be markedly more sluggish than in recent years.

… and policy rate cuts could then be in the offing

As far as the CBI is concerned, such responses would be conducive to policy rate reductions. If the real rate does not fall discernibly as a result of rising inflation and/or inflation expectations, it would be logical for the CBI to consider lowering the policy rate as the spring takes hold.

On the other hand, if wage settlements result in pay rises that firms cannot afford without substantially raising their prices, pressures on the ISK will grow stronger and the long-familiar wage-price spiral will develop, as it often has before. This will make it more likely that the CBI will push the real rate up in an attempt to shore up the credibility of the inflation target. Hopefully, it will not come to this.